A Parallel Notion, Plus Disco

The Wikipedia's entry on Watchmen contains this groovy tidbit:

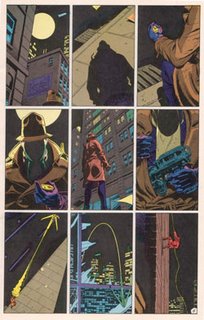

"Watchmen Observations" notes that Watchmen uses a three by three panel structure and that there is little variation in this format. The effect is to "reduce the scope for authorial voice--the reader has fewer clues how she should react to each scene; also, they heighten the feeling of realism and distance the novel from standard action comics."

and that there is little variation in this format. The effect is to "reduce the scope for authorial voice--the reader has fewer clues how she should react to each scene; also, they heighten the feeling of realism and distance the novel from standard action comics."

Hurm.

A cheap parallel came to my head: that the same description could be applied to soundtracks in movies. The rise-and-fall of intensity, the sudden rushes of feeling, and the changes-of-pace that comics express through panel shapes are more than a little like the same effects created in movies by their music.

Big scenes in movies are embiggened by music swells, and often musical cues are clues for the viewer to figure out how to react to a scene. (e.g., "Is the breakup scene funny or tragic? The dialogue is unclear, but the music is boppy. Ah ha! It's supposed to be funny!") Minimizing the music in a movie increases a sense of both realism and distance; heavy use of music creates deeper involvement in the action and a stronger emotional connection to the story.*

When our hero Dirk Squarejaw punches out a dude in the climax of Explodo Jones: The Quest for Ever More Radness, and the music is bopping along, it feels like no big deal. It's just Our Hero decking a dude. Replay the scene with brass and strings at high volume, the music peaking just as Dirk connects with a hook to the bad guy's head (BWAAAHH!! BWAAAHH!!), and it'll feel like A Very Big Moment. The audience will feel it in their guts.

The comic book adaptation of Explodo Jones: The Quest for Ever More Radness would show a minor dude's punchout in a small panel. A major villain's comeuppance via uppercut would take a splash page, the comic equivalent of a BWAAAHH!! BWAAAHH!! The reader will feel it in his gut.

That's my theory.

---------------

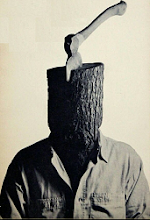

For your enjoyment, I give you: DISCO-DANCIN' FIRESTORM!

His head blazes! Blazes with a Disco Inferno!

And if I had Photoshop, I'd put him on a discotheque floor! But I don't! So instead he grooves in the inky blackness.

Go Ronnie! Go Ronnie!

---------------------------------

*The problem is that the emotions engendered by the music (or, one could argue, panel size and placement) are largely unearned. If the story requires musical cues to be effective, it's a crap story, isn't it? It should invoke its emotions without aid.

Then again, one could argue the same thing about any element in art. What constitutes illegitimate manipulation? The Dogme 95 movement rejects as many "artificial" elements from their films as they can, claiming that elements such as music, optical work, and special lighting are dishonest:

"As never before, the superficial action and the superficial movie are receiving all the praise. The result is barren. An illusion of pathos and an illusion of love."

Which sounds like a load of self-deluding twaddle to me, but there you go. The line between drama and melodrama, sentiment and sentimentality, is a matter of taste. Cartoon sound effects and thought balloons are rejected by most modern comic folk as "unreal," yet so are panels, cross-hatching, and a world that's drawn on paper. But at the same time, it's so easy to overuse emotion-creating effects and cheapen a work...gaaagh.

Drawing attention to the artifice of the panel by rejecting it in Watchmen invokes Brecht's alienation effect. Another nod to Brecht is the Black Freighter story-within-story, a recasting of Pirate Jenny in the Threepenny Opera. My ever-so-clever supposition? Moore liked Brecht. Yep.

"Watchmen Observations" notes that Watchmen uses a three by three panel structure

and that there is little variation in this format. The effect is to "reduce the scope for authorial voice--the reader has fewer clues how she should react to each scene; also, they heighten the feeling of realism and distance the novel from standard action comics."

and that there is little variation in this format. The effect is to "reduce the scope for authorial voice--the reader has fewer clues how she should react to each scene; also, they heighten the feeling of realism and distance the novel from standard action comics."Hurm.

A cheap parallel came to my head: that the same description could be applied to soundtracks in movies. The rise-and-fall of intensity, the sudden rushes of feeling, and the changes-of-pace that comics express through panel shapes are more than a little like the same effects created in movies by their music.

Big scenes in movies are embiggened by music swells, and often musical cues are clues for the viewer to figure out how to react to a scene. (e.g., "Is the breakup scene funny or tragic? The dialogue is unclear, but the music is boppy. Ah ha! It's supposed to be funny!") Minimizing the music in a movie increases a sense of both realism and distance; heavy use of music creates deeper involvement in the action and a stronger emotional connection to the story.*

When our hero Dirk Squarejaw punches out a dude in the climax of Explodo Jones: The Quest for Ever More Radness, and the music is bopping along, it feels like no big deal. It's just Our Hero decking a dude. Replay the scene with brass and strings at high volume, the music peaking just as Dirk connects with a hook to the bad guy's head (BWAAAHH!! BWAAAHH!!), and it'll feel like A Very Big Moment. The audience will feel it in their guts.

The comic book adaptation of Explodo Jones: The Quest for Ever More Radness would show a minor dude's punchout in a small panel. A major villain's comeuppance via uppercut would take a splash page, the comic equivalent of a BWAAAHH!! BWAAAHH!! The reader will feel it in his gut.

That's my theory.

---------------

For your enjoyment, I give you: DISCO-DANCIN' FIRESTORM!

His head blazes! Blazes with a Disco Inferno!

And if I had Photoshop, I'd put him on a discotheque floor! But I don't! So instead he grooves in the inky blackness.

Go Ronnie! Go Ronnie!

---------------------------------

*The problem is that the emotions engendered by the music (or, one could argue, panel size and placement) are largely unearned. If the story requires musical cues to be effective, it's a crap story, isn't it? It should invoke its emotions without aid.

Then again, one could argue the same thing about any element in art. What constitutes illegitimate manipulation? The Dogme 95 movement rejects as many "artificial" elements from their films as they can, claiming that elements such as music, optical work, and special lighting are dishonest:

"As never before, the superficial action and the superficial movie are receiving all the praise. The result is barren. An illusion of pathos and an illusion of love."

Which sounds like a load of self-deluding twaddle to me, but there you go. The line between drama and melodrama, sentiment and sentimentality, is a matter of taste. Cartoon sound effects and thought balloons are rejected by most modern comic folk as "unreal," yet so are panels, cross-hatching, and a world that's drawn on paper. But at the same time, it's so easy to overuse emotion-creating effects and cheapen a work...gaaagh.

Drawing attention to the artifice of the panel by rejecting it in Watchmen invokes Brecht's alienation effect. Another nod to Brecht is the Black Freighter story-within-story, a recasting of Pirate Jenny in the Threepenny Opera. My ever-so-clever supposition? Moore liked Brecht. Yep.

2 Comments:

He's a maniac.

A maniac on the floor.

By Brandon Bragg, at 8:22 PM

Brandon Bragg, at 8:22 PM

I... would buy Explodo Jones, if it existed.

By Bill Reed, at 1:33 PM

Bill Reed, at 1:33 PM

Post a Comment

<< Home