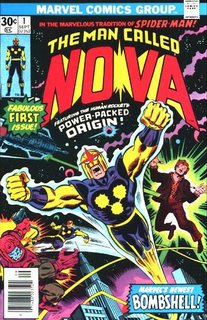

He’s ridiculous. No question.

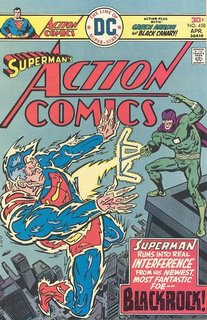

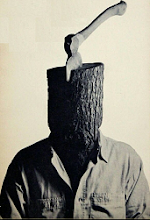

Green cape. Red costume. Yellow mask. The man looks like a crazy person, even by comic book standards.

And the name? Oh come on. Both his “superhero name” and “regular guy” name are absurd.

His gimmick? Weird.

And I love the demented bastard more every year.

Mister Miracle, Super Escape Artist. Known in private life as “Scott Free.”

Yeah, those are wacko names. But they make sense in context. The

Fourth World is all about context. And silly names.

In the early seventies, DC Comics put out a handful of interconnected series by Jack Kirby, creating a mythology out of whole cloth. He dubbed it “The Fourth World,” and it was powerfully nuts. Gods, wars, Manichean cosmologies, all sorts of big loud hoo-hah ran amok in those pages.

As my taste in comics runs towards low-powered superheroes and away from gods, it took me a while to appreciate what the Fourth World was about. It seemed pointless and silly. But it’s not just another set of alien worlds with powerful beings bashing in one another’s heads.

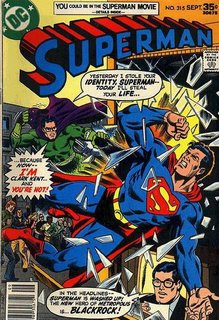

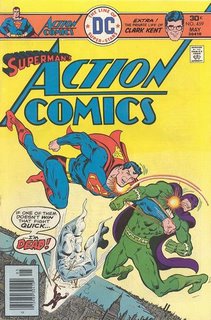

Traditional superhero comics introduce the fantastic into the mundane. Superman flies over the semi-real city of Metropolis, saving normal people. Spider-Man swings around New York City, stopping muggers. A large part of the appeal of such comics is the intersection between the everyday world and super-wackiness.

The Fourth World based itself around a different appeal. There were very few normal people in the comics, and they weren’t important. Instead, the mythology was self-contained and self-referential. The comics were, as odd as it sounds to say, a little abstract. The setting was an allegory, its own skewed reality. A big freakin’ Comic Book Opera, so to speak.

Two planets fight a never-ending war.

New Genesis is a pastoral planet filled with noble gods. Apokolips is its opposite; it is covered by massive industry and “fire pits” larger than continents. The worlds, made from the remnants of old gods long dead, war for control of the universe. Yeah, it’s big and woolly stuff.

The inhabitants of Apokolips are raised from birth to serve their one and only master, Darkseid. The goal of the evil god is rule over all life. What sets him apart from standard would-be conquerors is the depth of Darkseid’s ambition. He does not want only to rule; he wants to eliminate the very capacity for rebellion in his subjects.

Darkseid’s aim is to eliminate all free will and replace it with his own.

He fashioned Apokolips in pursuit of this goal, grinding out individuality, freedom, and hope from all of its inhabitants. The plot engine of the Fourth World comics is Darkseid’s quest for the “Anti-Life Equation,” an abstract formula which, if used, removed all free will from living things except the formula’s possessor. He knows it exists somewhere, and he intends to find it.

The main opponent of Darkseid is his own son, Orion. Orion, raised by the kind gods of New Genesis, grew to become a powerful warrior and the largest impediment to Darkseid’s schemes. Orion is a pretty cool character, and his recent eponymous series by Walt Simonson could only be described by the phrase “mind-blowing kickass comic greatness.”

Orion is one of my favorite series ever to reach print.

But this piece isn’t about Orion. It’s about his “brother.”

Mister Miracle is the son of Darkseid’s opposite number, Highfather, the peaceful leader of New Genesis. Just as Orion was raised on New Genesis, Scott Free was raised on Apokolips, traded with Orion as part of a pact to establish peace.

Scott was raised in “Granny Goodness’s Orphanage” to become a mindless soldier and worship the overlord Darkseid. But the brainwashing never worked completely, nor was Scott able to abandon his innate compassion. He slipped away from his barracks at night, he met with heretics, and worst of all, he dreamt of a better life, a life beyond servitude to Darkseid.

Scott became the only person to ever escape from Granny’s orphanage. He made his way to Earth and, through a weird set of circumstances, became an escape artist.

Kinda oddball, yeah.

What’s the big deal about Mister Miracle? What’s the appeal?

Orion is the physical opponent of Darkseid. He appears on the horizon, blows up the place, and leaves. His opposition is straightforward. He is force, pure and simple.

Mister Miracle, on the other hand, is Darkseid’s nightmare. On a planet designed to be a giant prison, who is more dangerous than the man who cannot be held? Apokolips’s empire needs fear and blind obedience. Scott Free is the man who is not afraid and will never obey.

Worse, he exposes the tyrant’s single weakness: that for all Darkseid’s efforts to abolish freedom and hope, he has failed. Scott went through the worst of Apokolips and came out a laughing freeman. He is the living proof that Darkseid cannot win. He is the symbol to the citizens of Apokolips that hope lives even in the dank corners of their world.

Orion is the reason Darkseid will die. Mister Miracle is the reason Darkseid will lose.*

That goofy bastard in the Christmas-colored suit and flying frisbees is the embodiment of freedom itself.

Spiffy.

Moreover, Scott Free has more to his story than his relationship with Darkseid. There’s his wife, Barda. Michael Chabon wrote an ode to Barda entitled “

A Woman of Valor” that describes her better than I could:

For now I’ll just say that Big Barda, commander of the Female Fury Batallion, was born and reared for a life of perpetual combat, on a world called Apokolips, by a Dickensian harridan with the cruel-irony name of Granny Goodness. She dressed in elaborate armor of dark blue scale mail with a vaguely pharaonic battle helmet, and carried a fearsome chunk of hardware, admittedly somewhat ambiguous from the Freudian point of view, called a Mega-Rod. As for her eponymous immensity, it was not merely physical; everything she did partook of the bigness that was the essence of her character. She spoke in exclamations and displayed Rabelaisian appetites for food and drink. She was brusque, sardonic, hot-tempered, and did not endure patiently the doubts and tergiversations of anyone less intelligent or quick to seize the moment than herself. And she was, to my knowledge, the first super-heroine in the history of comic books whose personal courage, moral integrity, and astute intelligence, though they pervaded all her actions, were most joyfully expressed through her willingness, when necessary, to kick ass.

…

Barda was up to the fight--any fight, and then some. The world she was born into and the way she was raised had obliged her to learn to be strong, vigilant, resourceful, and submissive to no one. But her intelligence told her that conflict is a waste, of life and time and energy, and she regretted it. She had her own narrative--a history of heartbreak, hardship and achievement--and though it constituted only one part of the larger mythology of Kirby’s epic, it was her part; she had earned it. She saw the wrongness, the wickedness, the unreasoning cruelty of the world, and though she had been trained to withstand it, her heart rebelled. Mighty, she used her strength and risked her freedom to help the weak. In time she would mutiny against the might-makes-right strictures of her home, and attempt to form a partnership of physical and intellectual equals--with Mister Miracle, her paramour, the love of her life. In his company, in rare moments of quiet, she doffed her armor, laid down her Mega-Rod, and made him a gift--both of them knowing full well its value--of her vulnerability, her sorrow, the pain of her childhood and youth. She was a valkyrie with a brain and an aching heart.

The history of comic book women, especially at the time of Barda's creation, is dismal. Submissive (“Invisible Girl?” “Shrinking Violet?”), secondary (Supergirl, Batgirl) or twisted (Wonder Woman began with a heavy bent towards bondage—really—and over the years has been warped and reformed so many times she’s never been much more than an image).** Barda was a tremendous break from the norm.

An undercurrent of control seeps into these earlier characters. The women are, in some sense, restrained, made to be less than what they could be. Relegated to be extensions of men, lesser and less powerful than the male characters, and sometimes just plain bitchy. Held back.

Big Barda was the first unapologetically powerful and independent woman in comics.*** Physically strong, brash but not bitchy, and not introduced for the purpose of cheesecake, she was, to use an antiquated but accurate term, liberated. As Chabon noted, she is that rarest of super-heroines, her own character.

Not long after her introduction, Barda chose to marry the man who could never abide one person controlling another, the man who would never ask her to be anything other than her full self: Scott Free.

The dynamics between the two are unusual in comics. Aside from the genuine partnership between them, a rarity in itself, Barda is by far the more physically powerful of the two. Scott is as strong as an athlete; Barda is as strong as a tank. He’s the deliberate planner, she’s the butt-stomper. And this doesn’t bother him in the least.

Throw in the intrinsic coolness of escape artistry, and there you have it: a great character.**** With a goofy-ass costume.

Walt Simonson’s recent series Orion ended with a guest appearance by Scott and Barda. In that issue, Simonson revealed the true hiding place of the Anti-Life Equation: within the brain of Scott Free.

The god of freedom contains within himself the means to end freedom, and he guards it carefully to prevent it from ever being used.

That’s excellent. And ridiculous. And forehead-slappingly over the top.

Thus, it fits with the rest of the Fourth World. I love it.

Rock on, you crazy Christmas-colored bastard. Rock on.

(The new version of Mister Miracle, part of Grant Morrison’s Seven Soldiers of Victory collection of miniseries, is also proving to be a hoot. But he’s a subject for another post.)

-------------------------

* Please pardon the purple prose. It’s difficult to describe the Fourth World books in any other way. They crank up the emotional and physical volume high enough to blow out speakers.

** Wonder Woman is a mess. From what I’ve gathered, her character’s been improved a lot over the last fifteen or twenty years, but most of her history? A mess. Check out Marionette’s magnificent history of Wonder Woman comics for proof.

*** No, I don't count Wonder Woman. Feel free to call me a dope and/or point out how I'm wrong. Until someone proves otherwise, I claim Diana may have became an independent and solid character eventually, but she wasn't one in 1970. (Odd note: In 1970 she was a de-powered kung fu superspy type.) If I'm wrong, well, then, crap. Substitute "Barda was one of the first..."

**** Escape artistry is wicked cool. A historical fact.

Click here to read more!

*

*