The cartoon sexuality of Red Sonja got me thinking about which women in comics appealed to yers truly.

Most comic book women were designed to appeal to men. Despite this, they almost always fail to leave any sort of lasting impression.

Then there are the women featured in Will Eisner's classic

The Spirit.

One reason for their lasting appeal lay in Eisner's art. His cartoony style allowed for a range of expression and emotion that gave the women distinct flavors. Not only did they simply look different from one another (a rarer condition for comic women than you'd think), they carried themselves differently.

Distinguishing one Jim Lee replicant-girl from the next is nigh-impossible unless you go by costume or hair color. Distinguishing Ellen Dolan from Nylon Rose from P'Gell? No challenge at all.

Eisner patterned many of his women on movie stars of his day. The brilliance of this plan was that it ensured each woman was beautiful in her own distinct way. Silk Satin was Katharine Hepburn; Sand Saref was Lauren Bacall; P'Gell was Marlene Dietrich. The cartoony abstraction of his art made the effect work, as he took only the rough outlines of the actresses and the essence of their appeal. Readers respond to the qualities of the actress, but aren't pulled out of the story by thinking, "hey, that's Rita Hayworth."*

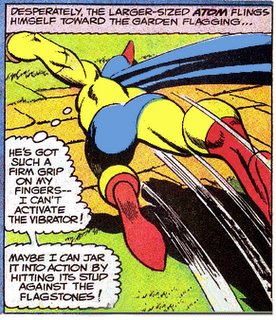

Consider that women designed to be sexually alluring fill the pages of many modern books. (Hey, an entire genre of comics are known, at least in my own head, as "Hello, Boobies!" comics.) Also, soap opera elements continue to abound in the four-color world. Despite both of these factors, romance itself in mainstream comics is rare. In

The Spirit, romance was a common subject. The titular hero's ongoing courtship of Ellen Dolan was a charming story element, and it was frequently complicated by the presence of other women vying for the hero's affections. (Though it must be noted that none of the others stood a real chance. The Spirit was a man who loved women, but he was not a cad.)

The romance was often fun, as well. The interplay between the Spirit and the women in his adventures tended to be playful and more than a little charged with sexual energy. Has there ever been a masked hero who has been portrayed covered in lipstick marks than the Spirit? That man's been kissed more than a president's ass.

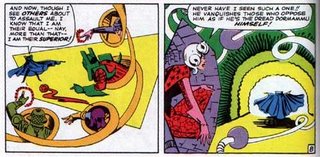

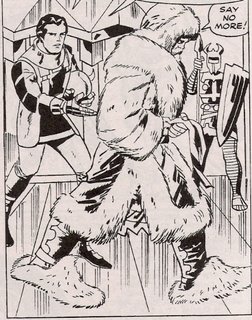

Romance infused one of the most famous scenes in

The Spirit's history, the climax of the first Sand Saref story. We read how Sand and Denny Colt grew up together in a rough part of Central City. Then one night Denny's uncle, a palooka working his first burglary, gets caught by a police officer and his best friend: Sand's father. To avoid capture, one of the thieves shoots Officer Saref. A few days later, Denny's uncle cannot take the regret and kills himself.

Out of the tragedy, Denny is driven to a life of law and order. Sand spurns that same law and order as false promises. He grows up to become a detective and later the Spirit. Sand grows up to become a criminal and a spy. After the war, she returns to Central City, involved in a deal for a secret chemical weapon. The Spirit intervenes, and the story ends thusly.** (click on the picture to enlarge)

The scene is cheesy, sure. Affecting and memorable as well.

Eisner wasn't afraid to have characters fall in love or show affection. Neither action is or was common in other comics, despite their value in developing characters and heightening reader interest. Placing his women in romantic lights, Eisner enriched and broadened their characters as well as increased their appeal.

It also made the Spirit himself a more involving character, but I'm writing about the ladies today.

The women of The Spirit demonstrated many sides of themselves within their stories. One issue centered on Silk Satin and her newly-adopted daughter, Hildie. Within a very few pages, Silk is shown as a mysterious spy, a rival for the Spirit's affections, a beautiful woman with a hint of goofyness, a doting mother, and, in the story's climax, a stone-cold killer when called upon to protect her child.

Her character varies within the story but within a believable range. That she can go from amusing come-ons to the Spirit to capping goons from the shadows makes her feel more real, more memorable.

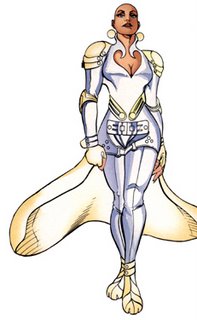

The modern comic conception of alluring women is rooted in simple physical aspects: big boobs, tight clothing, long legs. Most four-color women are an undifferentiated blur of fantasy elements, designed to appeal to one's glands. These characters tend to be simple and free from angularities. Smooth as billiard balls, their characters slip from your mind because there's nothing to hold onto.

The modern comic conception of alluring women is rooted in simple physical aspects: big boobs, tight clothing, long legs. Most four-color women are an undifferentiated blur of fantasy elements, designed to appeal to one's glands. These characters tend to be simple and free from angularities. Smooth as billiard balls, their characters slip from your mind because there's nothing to hold onto.

Eisner's approach was that a woman's attraction is in large part rooted in her personality, in who she is beyond the pretty face. Their rough edges and sharp angles make them easy to grip in your mind.

The Spirit's women linger in your head, each one her own character, reaching and inflaming different parts of your mind. Just like the real thing.

Will Eisner must have known and appreciated women. He created quite a batch of great ones.

Mmmmm...women.

--------------------------

*Photo-referencing pulls me out of stories something wicked. "Hey look, it's Clint Eastwood! No, wait, he's Jonah Hex. No, wait, he's Clint Eastwood playing Jonah Hex!" Gack.

**A young Frank Miller later swiped the story and adapted it to one of his first issues of Daredevil, changing Sand Saref into his signature character, the assassin Elektra. This is not a dig on Miller. It's a good story to use, he made it his own in Daredevil, and dang it, swiping from Eisner shows good taste. I only bring it up because Miller has credited the Sand Saref story in interviews.

Click here to read more!

How could I possibly have them? They are wrapped in mystery! Do they have vinyl non-skid soles? Or are they perhaps rubber? I do not and cannot know! And thus I am denied divinity!

How could I possibly have them? They are wrapped in mystery! Do they have vinyl non-skid soles? Or are they perhaps rubber? I do not and cannot know! And thus I am denied divinity!